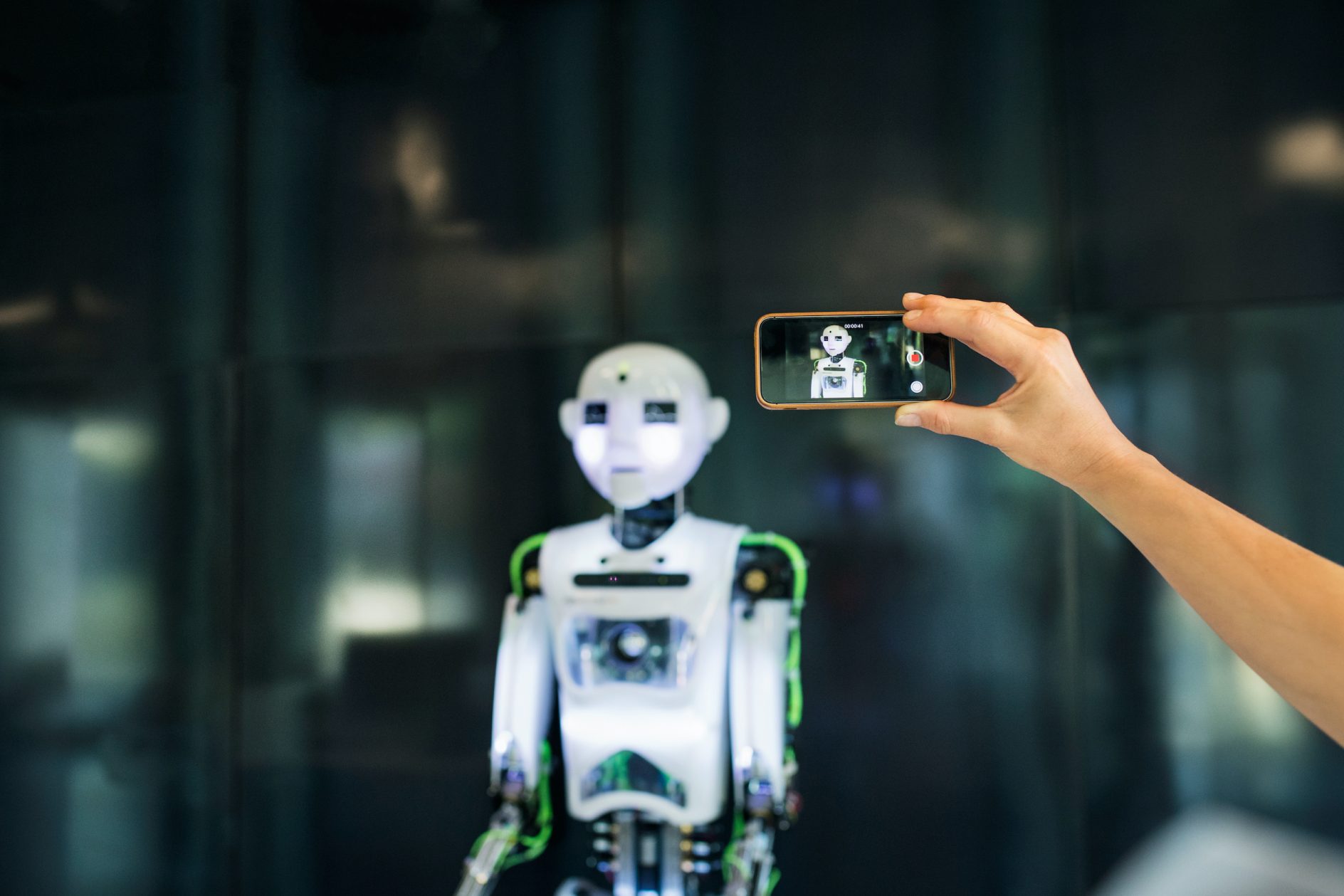

Will Robots Take Our Jobs?

هل ستأخذ الروبوتات وظائفنا؟

Reuters

More robots joined the U.S. workforce last year than ever before, taking on jobs from plucking bottles and cans off conveyor belts at trash recycling plants to putting small consumer goods into cardboard boxes at e-commerce warehouses.

It looks like still more robots will come aboard in 2022.

Companies across North America laid out more than $2 billion for almost 40,000 robots in 2021 to help them contend with record demand and a pandemic-fueled labor shortage. Robots went to work in a growing number of industries, expanding well beyond their historic surge in the automotive sector.

“With human labor, what they produce depends on if they’re hungry or are they tired or have they had their coffee,” said Brian Tu, chief revenue officer for DCL Logistics in Fremont, California, which started installing robots on e-commerce fulfillment lines during the pandemic. Robots are dependably fast and do not take breaks.

Factories and other industrial users ordered 39,708 robots in 2021, 28% more than in 2020, according to data compiled by the industry group the Association for Advancing Automation, also known as A3. The previous annual record for robot orders was set in 2017 – when North American companies ordered 34,904 robots valued at $1.9 billion.

As recently as 2016, more than twice as many robots were sold to auto makers as to all other industry sectors combined. But in 2020, other businesses eclipsed automakers as buyers of the advanced machines, and the share of robots going to non-auto companies grew further in 2021.

Some of the fastest growth in robot orders is in the metals and food and consumer goods industries, according to A3.

E-commerce is another fast growth sector. At DCL, which has five U.S. fulfillment centers and will soon open a sixth, the lines that have gotten robots can operate with fewer people – yet produce 200% more, according to Tu.

“We still have employees working around the robots,” he added, “but we can reduce labor by roughly half.”

BRING ON THE ‘COBOTS’

The A3 data mostly tracks orders for traditional industrial robots – large systems that typically replace an entire section of an assembly line with moving arms. But a growing share of robots are a new breed of “cobots,” designed to work alongside humans on assembly lines.

“The number one driver for automation is the labor shortage in manufacturing,” said Joe Campbell, a senior manager for applications development at Universal Robots, a unit of Massachusetts-based Teradyne Inc (TER.O), which specializes in cobots. And the pandemic is not the only factor driving the change. Universal estimates 2,000 Baby Boomers are retiring daily in manufacturing, robbing factory floors of veteran expertise.

Campbell said cobots are making inroads into many industries that long resisted automation. In construction, for instance, the company has sold robot arms to a firm that uses them to install drywall in large building projects: a notoriously labor-intensive process.

Auto plants are also finding new uses for cobots. Stellantis N.V., the Dutch automaker, is now using Universal’s cobots in the final assembly area of its factory in Turin, Italy, to help produce the new Fiat 500 electric vehicle. The arms are attached to a framework that moves over the car, where they locate and fasten nuts, said Campbell.

While auto plants have used robots for decades to do jobs like weld metal, he said, it is “very new” for cobots to do final assembly jobs.

Last week, Tesla Inc (TSLA.O) Chief Executive Elon Musk said his engineers would launch a humanoid robot called Optimus in its factories next year. In the short term, Musk said these robots might carry items around a factory and could eventually address labor shortages.

As of December, U.S. employers had 10.9 million vacant positions, nominally below the record 11.1 million from earlier in 2021. There are now an unprecedented 1.7 open jobs for every unemployed worker, and at least one policymaker at the Federal Reserve – St. Louis Fed President James Bullard – sees the U.S. unemployment rate dropping below 3% this year for the first time since the 1950s.

“Never say never,” said Universal Robots’ Campbell, “but I don’t see anything to slow us down.”

رويترز

تولى عدد أكبر من الروبوتات وظائف تراوح بين التقاط الزجاجات والعلب الصفيح من فوق السيور في منشآت إعادة تدوير القمامة، ووضع سلع استهلاكية صغيرة في صناديق من الورق المقوى في مستودعات التجارة الإلكترونية، لتشغل بذلك نسبة أكبر من سوق العمل الأمريكية العام الماضي مقارنة بأي وقت مضى.

ويبدو أن مزيدا من الروبوتات سيقتحم سوق العمل في 2022، إذ أنفقت الشركات في أنحاء الولايات المتحدة أكثر من ملياري دولار على شراء نحو 40 ألف روبوت في 2021 لمساعدتها على مواجهة معدلات طلب قياسية ونقص اليد العاملة الناجم عن الجائحة.

ووفقا لـ”رويترز”، تولت الروبوتات مهام في عدد متزايد من الصناعات، وتوسعت إلى ما هو أبعد من وجودها غير المسبوق في قطاع السيارات.

يقول بريان تو المدير التنفيذي البارز في شركة دي.سي.إل لوجيستكس في ولاية كاليفورنيا، التي بدأت الاستعانة بالروبوتات في قطاع التجارة الإلكترونية خلال الجائحة “بالنسبة إلى العمالة البشرية، يعتمد معدل إنتاجهم على إذا ما كانوا يشعرون بالجوع أو التعب أو حتى إذا كانوا قد تناولوا قهوتهم”. في المقابل، الروبوتات سريعة على نحو يعول عليه، ولا تأخذ فترات راحة.

ووفقا لبيانات جمعتها مجموعة الصناعة المعروفة باسم جمعية تطوير الأتمتة، فقد طلبت المصانع وغيرها من المستخدمين الصناعيين شراء 39708 روبوتات في 2021، بزيادة 28 في المائة عن 2020. وكان الرقم القياسي السنوي السابق لطلبات الروبوت قد سجل 2017 عندما طلبت شركات في أمريكا الشمالية 34904 روبوتات بقيمة 1.9 مليار دولار.

حتى 2016، كان عدد الروبوتات التي اشترتها شركات صناعة السيارات يتجاوز ضعف عددها في جميع القطاعات الصناعية الأخرى مجتمعة. لكن في 2020، تفوقت الشركات الأخرى على شركات صناعة السيارات في شراء الروبوتات. وزادت حصة الروبوتات التي ذهبت إلى الشركات غير المتخصصة في صناعة السيارات بشكل أكبر في 2021.

وتقول جمعية تطوير الأتمتة “إن صناعات المعادن والأغذية والسلع الاستهلاكية تشهد نموا أسرع من غيرها في طلبات الروبوتات”.

كما أن التجارة الإلكترونية من بين القطاعات التي تشهد اعتمادا متزايدا على الروبوتات.

ويقول تو “لا يزال لدينا عمال يعملون بجانب الروبوتات، لكن يمكننا تقليل العمالة بواقع النصف تقريبا”.

من جهة أخرى، يعطي تطبيق “تيك توك” للتواصل الاجتماعي منذ أشهر دفعا للتحولات الحاصلة في سوق العمل الغربية، عبر تقديم محتوى يدرب على كيفية تقديم استقالة من عمل، أو نصائح عن كيفية التفاوض بصورة أفضل على الراتب، أو كيفية البحث عن المعنى الحقيقي وراء اختيار المهنة.

ولعل ظاهرة تصوير الاستقالة وبثها مباشرة عبر الشبكة تجسد بوضوح هذه الحملة، فمنذ 2020، استخدم عدد كبير من مستخدمي التطبيق البث المباشر لتصوير أنفسهم وهم يغلقون الباب وراءهم بينما يتركون المؤسسة التي يعملون فيها.

وأطلقت هذا التحرك الشابة الأمريكية شانا بلاكويل “19 عاما” في تشرين الأول (أكتوبر) 2020، عندما أعلنت في مقطع فيديو ترك عملها في “وول مارت” بتصريح عبر مكبرات الصوت في المتجر، قالت فيه “تبا للمديرين، تبا لهذه الشركة، أنا أستقيل”.

ووفقا لـ”الفرنسية”، أوضحت بلاكويل أنها أمضت عامين صعبين في المتجر تحت ضغط مضايقات معنوية جمة.

وأطلقت الموظفة السابقة من دون أن تقصد، إحدى أكبر الموجات على المنصة. ولقيت مقاطع فيديو مرفقة بوسم QuitMyJob# “أترك عملي” منذ ذلك الوقت أكثر من مائتي مليون مشاهدة.

وتلقى مقاطع الفيديو هذه صدى كبيرا في الولايات المتحدة، حيث تنتشر موجة غير مسبوقة من الاستقالات، أطلق عليها اسم “الاستقالة الكبرى”، وبشكل أقل نسبيا في فرنسا.

وترى ستيفاني لوكاسيك، الباحثة في الإعلام والتواصل في جامعة لورين في شرق فرنسا، أن نتيجة هذا التداول تمثلت في مزيد من الاستقالات المرتبطة بـ”التأثير القوي للتقليد”، حتى لو كان يصعب قياس أثرها بدقة.